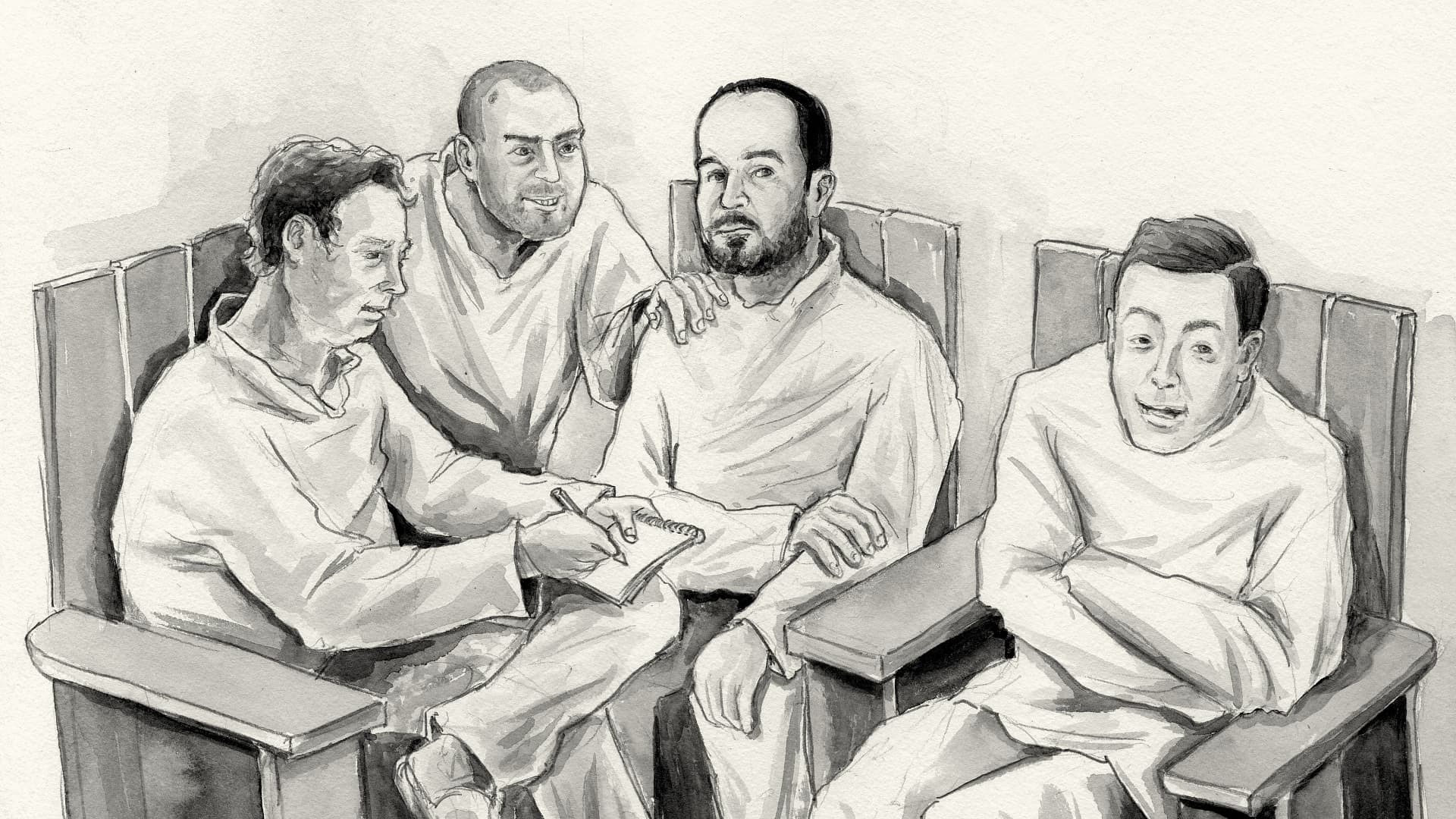

In 1972, Dr. David Rosenhan, a psychiatrist at Stanford University, conducted a controversial experiment that caused a stir in the field of psychiatry. He wanted to measure the effectiveness of psychiatry in treating mental illnesses. So, he and seven of his doctor friends decided to go to psychiatric hospitals and clinics and behave completely normally. They would tell the doctors that they were hearing voices and seeing things, to see if the doctors would recognize that they were fake patients pretending to be mentally ill, or if the psychiatry they practiced would fail to distinguish between a normal person and someone pretending to be ill.

Anyway, they took some of them and went. All the hospitals they visited diagnosed them with schizophrenia and admitted them to the hospital, prescribing them medication until they recovered. The other group were regular people who lied, pretending to be ill, and they wanted to see if the doctors would figure out that they were not actually sick or if the psychiatry they practiced would fail to distinguish between a normal person and someone pretending to be ill.

When these doctors entered the hospital, they took their medication and threw it away. After a while, they went back to the doctors and told them, “We feel better now and we think we can leave.”

The strange thing is that the hospitals refused to discharge them and told them, “No, you’re still sick.” “But I’m fine,” they would say. The hospital would reply, “No, you stay. How do you know you’re fine? You’re still sick.”

Dr. Rosenhan, in an interview with the BBC, said that he had imagined that he could leave whenever he wanted, and he did not expect them to force him to stay in the hospital for two whole months just to be discharged, even though he was a normal person.

They did this with 12 other hospitals in 5 states, including public and private hospitals, and all of them diagnosed them with schizophrenia or other mental illnesses.

When this experiment ended, Dr. Rosenhan published it in the American journal Science under the title “Being sane in insane places,” suggesting from this experiment that modern psychiatry does not have strong methods and evidence to diagnose mental illness, which would enable it to determine the medication for the patient.

He wondered, since there are no strong bases through which we can diagnose mental illness like the bases through which we diagnose organic diseases, who proves that the diagnosis of these hospitals is correct?

After publishing this experiment, psychiatric hospitals and clinics were put in a very awkward position. How could they accept sane people as patients?

However, some of these hospitals challenged Rosenhan to send them fake patients, and they would discover them. Rosenhan accepted the challenge and told them, “In the next few weeks, I will send you people, and you should let them out if your claim is true!”

After the period passed, the hospital sent him 41 people, saying, “Here you go, Doctor. Your fake patients are important.” Rosenhan replied, “I didn’t send anyone in the first place.” How?

For a long time, there has been a large opposition movement against modern psychiatry called the anti-psychiatry movement, and on the other hand, there are people who defend it with numbers and statistics.

Here we present both sides and talk about this old conflict.

The conflict began in the 1960s, which is the same period when psychiatric medications appeared and doctors began prescribing them to their mentally ill patients.

The opposition movement has more than one argument, including that the history of the emergence of psychiatric medications is not reassuring, according to their view… Why?

In the past, people believed that mental illness was caused by infection or an imbalance in bodily fluids, so they treated it by bleeding people, aiming to restore balance in the person’s body. Then, as medicine evolved, they started removing the tonsils, spleen, and even parts of the brain.

As medicine advanced further, they began treating it by balancing brain chemistry. However, the opposition movement does not see a difference between all these treatment methods used by psychiatrists. They argue that there is no scientific basis for diagnosing the patient, which means there is no way to measure the effectiveness of the treatment, according to Dr. Thomas Szasz, a professor at New York University, in his book “The Myth of Mental Illness.” He argues that to consider something a disease, certain criteria must be met, such as the presence of a specific disorder or pain in a specific organ like the liver or the brain.

Thomas argues that the mind is not an organ, so how can we say it is sick? He also says that there must be a scientific, biological method through which we can measure the disease. This means that someone with this disease should have certain cells in a certain density that prove he is sick, in other words, there should be numbers.

Many scientists began to take this view more seriously and started searching for tangible evidence of mental illnesses to be able to treat them. For example, the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin spent a long time of his life researching the brain and mental illness, looking for tangible organic changes in the brain that could be used as evidence that a person is mentally ill. However, he found it difficult to differentiate between a normal condition and a mental illness.

Dr. Richard Lane, an opponent of psychiatry, criticized psychiatrists for creating “medical names” for suffering that occurs in normal life. He also accused them of exploiting these medical names to create and sell drugs, even if these drugs were made from addictive substances like cocaine. Sigmund Freud played a major role in this, as he was a lover of cocaine. He believed that cocaine was effective in treating both mental and physical illnesses.

Freud published a study titled “About Coca,” which led some pharmaceutical companies to exploit the study and manufacture a drug from cocaine, claiming that it treated both physical and spiritual problems. However, due to cocaine’s bad reputation, this attempt failed.

In 1945, SmithKline and French introduced a new treatment called Thorazine for diseases such as schizophrenia and anxiety. The company launched massive marketing campaigns for this drug, instructing its representatives to work like soldiers in war. This campaign was highly successful, leading to the widespread use of this drug.

The use of Thorazine spread until there were more than 250 million people using it, leading to a 500% increase in the company’s sales. The drug alone accounted for more than a third of the company’s sales, prompting many pharmaceutical companies to think about manufacturing psychiatric drugs as a source of enormous profits.

This led to an attack on Thorazine by scientific platforms, and the government began to restrict its use to hospitals, creating a new challenge for pharmaceutical companies to produce a new drug with safe specifications for a wider range of people.

Two years later, a new product called Miltown was introduced to the world, becoming so popular that it was prescribed in about 36 million prescriptions in the United States alone, generating sales of around $200 million in a very short period. This led to the emergence of similar drugs like “Valium,” with 2 billion pills sold in one year. However, newspapers and media outlets criticized these drugs for causing side effects in many cases, prompting the chairman of the Drug Advisory Committee to state that these drugs were more dangerous than cocaine.

Despite these claims, pharmaceutical companies ignored them and continued to produce the drugs. Strangely, new psychiatric disorders appeared that were not present before, increasing the number of people suffering from mental illnesses. This prompted the opposition movement to call for treatment through other methods, such as yoga, group therapy for schizophrenia patients, and activities to improve their mental health.

As for Freud’s movement and supporters of psychiatry, they argued that the Industrial Revolution and economic progress over the past fifty years had made people more comfortable and less prone to organic diseases. However, it made mental thinking more common because routine work leads to increased thinking and anxiety, in addition to technological advancement, the spread of media, bad news, and violence, which increased cases of mental illness. This confirms that we are not the ones contributing to the increase in diseases, but rather it is reality that raises the percentage of patients.

In a 2017 study, it was found that the number of children admitted to psychiatric hospitals for suicidal tendencies doubled over a period of 10 years. Many studies have linked material progress with psychological frustration, leading to a need to label these symptoms as diseases.

Regarding the description of psychiatric drugs, supporters of Freud’s theory and psychiatry believe that the first step in diagnosing a patient is to look at their suffering from organic diseases, as many psychiatric cases are caused by physical illnesses. This is why psychiatrists prescribe drugs that act on hormone receptors in the brain, as depression may be caused by a deficiency in specific hormone receptors in the brain, which these drugs strengthen and increase.